The online reaction to the on-pitch performance of Marcus Rashford, Jadon Sancho and Bukayo Saka during the Euro 2020 final galvanised attention on online hateful abuse. During the final HateLab monitored posts sent to all ethnic minority players. The analysis of these posts was published as a postscript to The Science of Hate:

July 11 2021 was unlike any other Sunday that year for the HateLab team. At around 7:00 p.m. we gathered in a small darkened room, all of us knotted in front of a bank of computer monitors. At the flick of a switch, our faces began to glimmer as they reflected back the dazzling light emanating from the floor-to-ceiling array of screens. Charts displaying social media data streaming in live flickered onscreen – a ‘situation room’ for monitoring online hate in real-time. We had come together in anticipation of the largest volume of online hate posted on social media in the history of the lab’s existence: the UEFA Euro 2020 final at Wembley stadium.

Emotions were running high. England had bucked their historic trend all tournament, beating Germany, Ukraine and Denmark to get to the final. It felt like England’s best chance to end their five-decade wait for a major victory on the international stage.

The conditions on that night met all of our expectations for an explosion of online negative sentiment – and possibly hate – should the sorely sought-after victory slip though England’s fingers. England’s previous string of tournament losses to Italy ensured the ingroup and outgroup were firmly established, the threat and its consequences were abundantly clear, the stakes of the competition high, years of hurt felt by fans still alive in collective memory, and the chatter on social media polarising. This was a tinderbox for xenophobic hate, but the eventual targets were not who we had anticipated.

The game opening was electrifying for England’s fans, with Gareth Southgate’s team tearing out of the blocks and scoring in under two minutes. But it wasn’t long before Italy dominated possession and eventually equalised. In familiar fashion, the game ended in the ultimate test of nerve – a penalty shootout. In anticipation, Southgate had made substitutions late in extra time, sending on two young black players: Marcus Rashford and Jadon Sancho. Both, along with another black player, Bukayo Saka, missed their penalties, leading to England’s defeat.

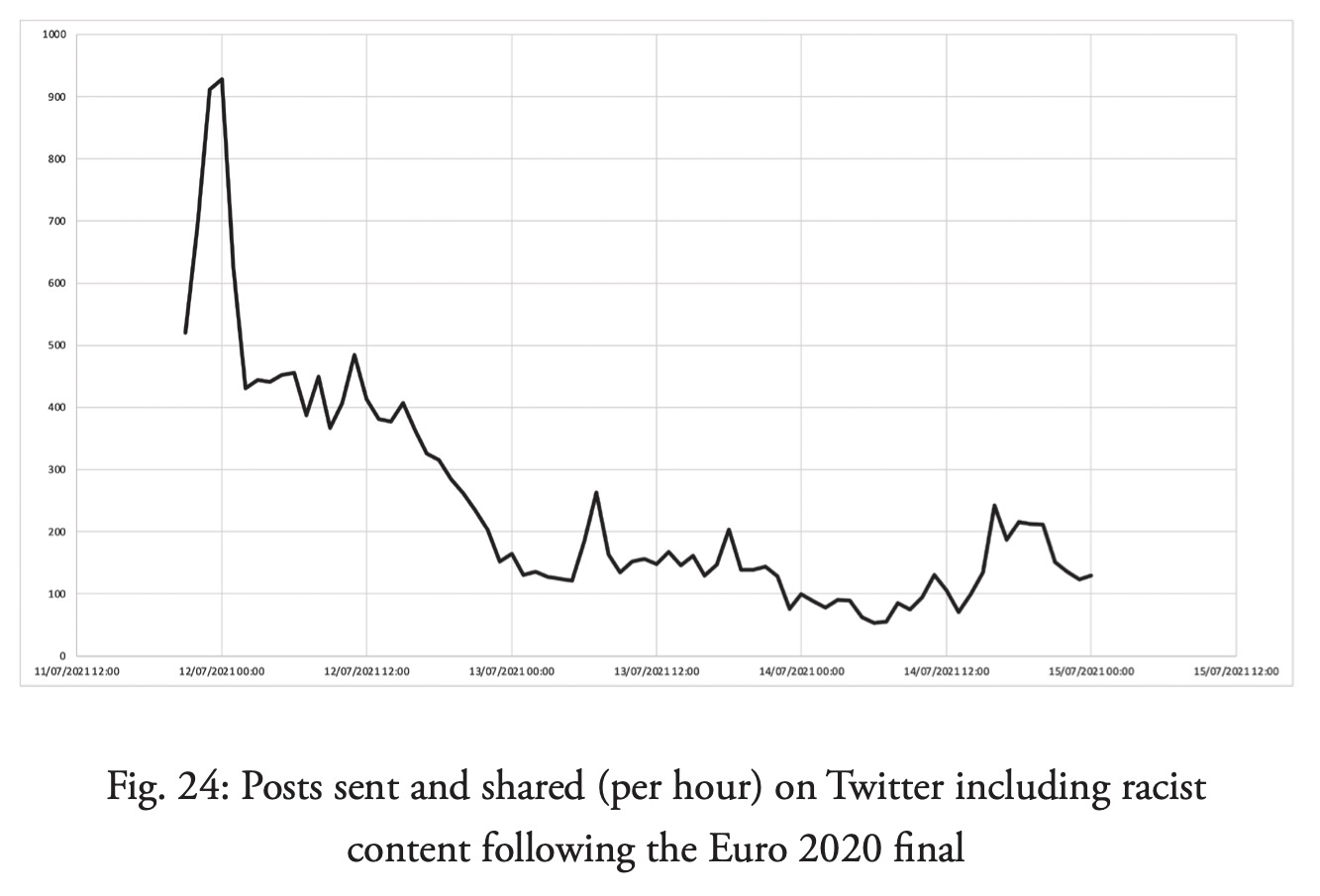

We had anticipated a minority of England fans posting online hate speech directed at Italy’s players, but instead the events near the end of the game saw them turn on their own. Within minutes of the penalty misses the number of racist posts sent and shared on Twitter skyrocketed, peaking at over 920 between 11:00 p.m. and 12:00 a.m. just after the game. Rashford, Sancho and Saka were the prime targets.[1]

The situation room display screens flooded with racial slurs and primate emojis. Twitter wasn’t the only platform to host the bile, and Instagram, Facebook, and many others allowed thousands of racist messages to be posted. In the subsequent days each platform claimed to have removed the most egregious violations of their community standards. Our analysis showed a different picture, with many harmful posts remaining online months after the game.

In the aftermath of the surge in online hate, complaints were filed and police reports were made. Police in the UK manually looked through tens of thousands of posts from across platforms. The Football Policing Unit received 600 reports and determined 207 to be potentially criminal. But only fifty-five of these were put forward for investigation as the majority of the incidents had emanated from overseas.[2] Only eleven arrests were made, and by November 2021 just three convictions had been successful.

Scott McCluskey, a forty-three-year-old from Runcorn, Cheshire, was at home watching the final with his son and partner. Purportedly fuelled with alcohol and cannabis, McCluskey took to Facebook following the penalty shootout and posted the racist comment, ‘Well it took three ethnic players to fuck it up. Unlucky England. Sack them three monkeys though.’ In his defence he stated he wrote the post to make people laugh. In court he pleaded guilty to sending by a public communication network an offensive message. He was given a suspended sentence of fourteen weeks imprisonment.

Following the game, Bradford Pretty, a forty-nine-year-old from Folkstone, Kent, recorded his reaction and uploaded it to Facebook. Heavily intoxicated with a smudged England flag painted across his face, Pretty slurred, ‘Where do I start, where do I start? Sick, gutted like all of us. Proper deflated. Be proud of the boys, be proud, but anyone and everyone that knows me well will understand what I’m talking about.’ He then went on to use two racist slurs while referring to Rashford, Sancho and Saka. In his defence his solicitor said it was a ‘moment of drunken madness.’ He was found guilty and sentenced to fifty days of imprisonment, suspended for twelve months.

Fifty-two-year-old Jonathan Best of Feltham, London, took to Facebook after imbibing a dozen beers to post an eighteen-second video blaming the loss on ‘three black cunts who can’t play for fucking England.’ Best was asked to remove the video after his colleague reported it to his boss. In response, Best said ‘It’s my profile, I can do what I fucking want.’ During sentencing the judge said Best ‘cursed them because of the colour of their skin’ and that his words ‘strike at the very nature of civilised society and are corrosive . . . encourag[ing] those who want to express similar views.’ A suspended sentence was considered, but the judge decided only an immediate imprisonment for ten weeks would suffice to deter others from similar acts of hate.

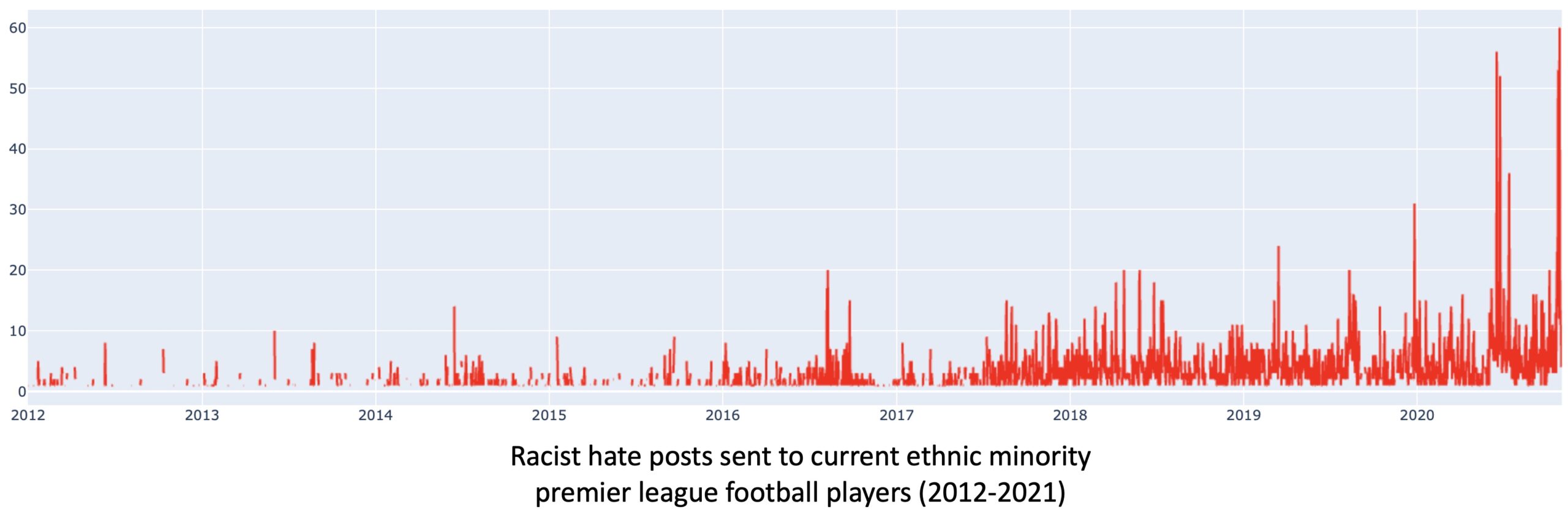

Since the start of the coronavirus pandemic the grisly problem of online abuse targeted at Premier League football players seemed to have accelerated, possibly fuelled by an increased use of social media around games due to the ban on stadium attendance. But HateLab analysis shows the problem has a long history.

In a groundbreaking study we collected every undeleted Twitter post sent over the last decade to an ethnic minority Premier League player active in the 2020/21 season.[3] Naturally we found more online racism in recent years, given our focus on current players. Some players came into the firing line more than others, sometimes due to poor performance on the pitch, but mostly because of their bigger profiles and their actions related to standing up to racism; racist posts were also more prevalent in recent years due to the trend in players taking the knee following the murder of George Floyd in May 2020. Based on our estimates, around 40 per cent of posts sent in the ten-year period originated from accounts claiming to be based in the UK.

What we also noticed were surges in hate dating back between five and ten years. When we included some retired ethnic minority premier league players, it became evident that there was little novel about the most recent spikes in online racism.

We took Rio Ferdinand as a case study and found he had received significant amounts of online racism on Twitter between 2011 and 2014, at points exceeding the massive surges seen in 2020.[4] These included the tweets, ‘@rioferdy5 honestly why didn’t ur mum have an abortion, your such a useless ugly nigga shit on the pitch look like a donkey nd thick as shit’, and ‘@rioferdy5. You fuckin black donkey why didn’t you shake @luis16suarez hand? Your a fuckin black cunt, get that?’ Sent in 2012, both remain on Twitter at the time of writing.

Some of the hateful posts sent to Ferdinand emanate from accounts that lack user detail, making it difficult to tell ‘real’ accounts – with actual identifiable people behind them – from fake or bot accounts. This makes the job of law enforcement hunting down culprits near impossible, especially when social media companies fail to cooperate in a timely manner, if at all.

Online hate targeting Premier League players is nothing new, but the actions of several players following the Euro 2020 final has galvanised the attention it has received. The abuse of Rashford, Sancho and Saka acted as a lightning rod for calls to governments to introduce serious consequences for social media companies that fail to deal with hate posted on their platforms. If law enforcement is operating with one hand tied behind its back, then surely the social media companies should step up and take some of the responsibility. Some big names in the sport have called for a ban on anonymous social media accounts, and a strengthening of laws to fine platforms for not removing hateful content.

These touted solutions are likely unworkable. Banning anonymity risks stifling the freedom of expression social media affords citizens living in repressive regimes, and it is unlikely that users would trust platforms with their government identity documents following the string of mass data leaks and misuse of data scandals. A ban on anonymity would therefore see platforms’ profits tumble as users left in droves.

Imposing large fines on platforms that refuse to remove hate speech will only work in a limited number of cases. It is likely that the hate speech would have to be clearly criminal in nature to issue a take-down notice, leaving a wide array of offensive content untouched. A time frame of twenty-four hours for removal, as has been suggested by some, also means the damage is likely already done to the victim and the wider community. Any move to compel platforms to prevent posting using some form of technology, such as machine learning, would also likely fail given the difficulty in automatically detecting hate speech and distinguishing it from non-hate speech that has a similar form, such as some counter-speech. Even improvements in prosecutions are unlikely to deter the most hardened haters, or those who post in the heat of the moment.

The solutions proposed by politicians, pundits and players are way off-target. This issue is not a technical one, but a social one. Together with the government and platforms, we too must take a stand against hate.

In addressing all online hate, we should turn our attention to the true great successes of the internet, digital commons. We have the ability to coordinate in powerful ways to stop online hate. In the face of hate and abuse, counter-speech that reinforces community standards can change online behaviour, and perhaps the minds of those behind the screens. HateLab research shows that when groups stand-up to online hate speech the chance of further hate is reduced.[5]

Those that care the most about football need to become hate incident first responders, setting and enforcing the standards of acceptable behavior both online and in stadiums. While this may be the more difficult of the proposed solutions, it will surely be the most effective and long-lasting should we enact it.